07/07/2020 05:23:10 PM

Books & Beyond

|

|

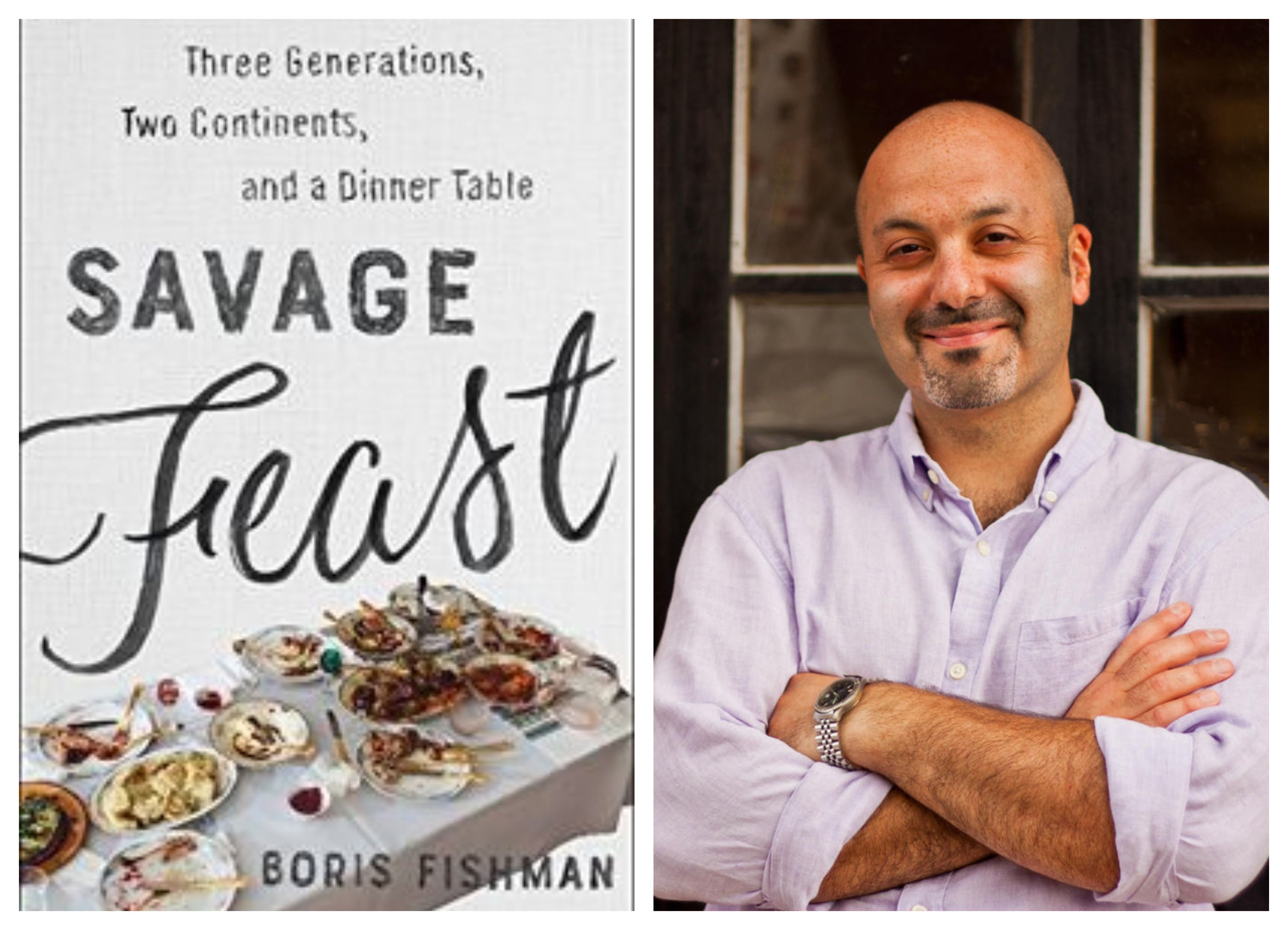

Always an ImmigrantBy Robin Jacobson As Moses might have said, “You can take the Jews out of Egypt, but you can’t take Egypt out of the Jews.” It is hard to shed a past life and homeland, even one of misery and persecution. This is the theme of two outstanding books by Jewish émigrés from the former Soviet Union: Savage Feast: Three Generations, Two Continents, and a Dinner Table (A Memoir with Recipes) by Boris Fishman, and Immigrant City, a short story collection by David Bezmozgis. |

|

Savage FeastOn Thanksgiving Day, 1988, nine-year old Boris Fishman arrived in the United States with his parents and grandparents, immigrants from Minsk, Belarus. Fishman’s debut novel, A Replacement Life, presented a fictionalized version of family members portrayed in Savage Feast. This engrossing memoir is about Fishman’s hunger – hunger for the mouthwatering epic meals conjured by the family’s “kitchen magicians” (recipes included), hunger for understanding and approval from his family, hunger to find a life partner. These hungers have roots in a darker hunger bred in the Soviet Union. During World War II, Fishman’s grandmother, Sofia, fled the Minsk ghetto to hide for two years in the Belarus swamps, subsisting on potato peels. When she first saw a loaf of bread after the war, “she tore at it like an animal,” making herself sick. Not surprisingly, Sofia married Arkady, a resourceful black marketeer able to obtain plentiful food and consumer goods even in a Soviet society of scarcity. Nonetheless, the family lived with the constant fear of not having enough, as well as with pervasive anti-Semitism. In the United States, Fishman’s family retained their Soviet mindset; they remained risk averse and apprehensive, always expecting the worse. Planning a family trip, Fishman fielded anxious questions from his father: “What if it snowed the night before we were supposed to go? What if the weather was bad? What if the hotel was no good?” When Fishman wanted to study abroad or accept a Fulbright fellowship in Turkey or relocate to Mexico, the family was so alarmed that he, nervous himself, turned down these opportunities. Yet Fishman insisted on becoming a writer, despite the family’s bewilderment and concern over such a financially unstable career. Savage Feast portrays Fishman as riven in two, loving his family, but resenting their Soviet pessimism and anxiety, which he couldn’t help but absorb. As Fishman says, he still feels “foreign in America.” |

|

Immigrant CityNearly 40 years ago, David Bezmozgis, age six, immigrated to Toronto with his family from Riga, Latvia. And yet, in a recent interview, Bezmozgis, sounding like Fishman, admitted that doesn’t feel fully Canadian. Bezmozgis has written extensively on what it means to come from one country but live in another (Natasha and Other Stories, The Free World, The Betrayers). Much of this work has focused on newly arrived Soviet Jewish immigrants. In contrast, Immigrant City, Bezmozgis says, is largely about immigrants “who have been here long enough to adapt,” but don’t adapt. Immigrant City opens with a story about a Latvian émigré and his young daughter journeying to a seedy neighborhood in Toronto to buy a replacement car door from a Somali refugee. The émigré’s American wife, “raised in mindless California abundance” fails to see the necessity for this bargain-hunting trek. But the émigré, who grew up eating spotted, less-than-perfect fruit, persists. The Somali’s neighborhood reminds him of the Toronto immigrant neighborhood where he grew up, and his suspicion of the Somali is leavened by feelings of solidarity. This story and others in the collection show immigrants continuing to grapple with their identity years after crossing the border. |